- Home

- Ben Fergusson

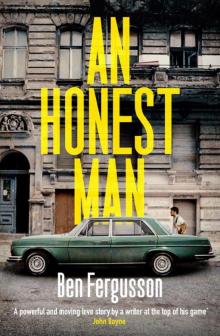

An Honest Man

An Honest Man Read online

Also by Ben Fergusson

The Spring of Kasper Meier

The Other Hoffmann Sister

Copyright

Published by Little, Brown

ISBN: 978-1-4087-0894-1

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Little, Brown

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

Contents

Also by Ben Fergusson

Copyright

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Acknowledgements

For Mum, Dad, Sam and Katie-Jane

The Athenians watched askance as Diogenes wandered about the city in broad daylight with a lit lamp in his hand. When he was asked by the gawping crowd what he was doing, he replied, ‘Why, I am looking for an honest man.’

One

When I was still a geology student it terrified me, shucking open a chunk of mud-black shale to find a single fossilised ginkgo leaf. It was the idea of it falling onto the soft silt of a Pangaean river, sinking, compacting and finding its way into my hands 270 million years later. All that time compressed in hot darkness – it made me claustrophobic. But now it consoles me. When I have to listen to someone clipping their nails on the U-Bahn or watch shouting demagogues on TV dressed in ill-fitting suits, I think of molten rock, ice and pressure, that our short time on earth will go the way of the ginkgo leaf – a few flat impressions in a split black rock.

The Berlin Wall too is a trace now, a faint line of cobbles at Potsdamer Platz, a toothy wall of rusted rebars along Bernauer Straße marking the brief division, one of any number of divisions in the city and, viewed from a distance, the least important. For centuries the river was the deadly barrier, when the first Berliners and their cattle were sporadically swept from the shallow ford after a hard winter and a warm spring brought torrents heaving down the valley from the Lusatian Highlands.

From the geologist’s point of view, the greatest division is the oldest and most enduring: the great glacial valley that Berlin fills, a valley carved out, not by the glacier itself, but by the meltwater that poured from it as it retreated north. In life as it is lived, though, perspective is lost to us. Most Berliners feel the valley’s sides only unconsciously when they haven’t turned the pedals of their Dutch bikes for a few minutes, descending from Prenzlauer Berg, Schöneberg or Kreuzberg – mountains all – into the valley bottom below.

Even in that final summer of 1989, when West Berlin was still the lopsided half-city of my childhood and the Wall still a 155-kilometre physical reality, it was only a trace to me. I sometimes caught sight of its graffitied face lurking at the end of a street like a fugitive, but it was no more striking than the shoes and handbags in glass vitrines on Kurfürstendamm; the punks at Kotbusser Tor asleep on benches, stinking of leather and vodka; the scrubbed concrete buildings of Ernst-Reuter-Platz topped with endless luminous letters – AEG, Osram, Leiser, Telefunken, Scharlachberg – and the circular signs of Bayer and Mercedes turning incessantly, like coins spun on their edges.

I remember clearly the dense heat of the dining hall at the Berlin British School where I did my A-level exams, my grey polyester trousers damp and pinching. I remember the packet of Polos peeled open on the graffitied ply of the exam desk, and the smell of the school hall: plimsolls, Dettol and savoury mince. I remember waiting in the underpass by Berlin Zoo Station by a Beate Uhse sex shop, avoiding the glances of prostitutes and tramps while my friend Stefan earnestly bought his first pornographic VHS tape (which he later binned in a pique of feminist solidarity). I remember the tallies with the Wildlife Trust, the silver fish skin of the goggle-eyed sunbleaks that my friends and I counted in red buckets at Riemeisterfenn, the grey herons we counted at Grunewaldsee and the bog rosemary we counted at Hundekehlefenn, crushing the pink bulbs between our pink fingers as the morning sun bleached the alders and turned the silver bark of the birches the pinky orange of melon flesh.

And I remember Prinzenbad public baths, three huge outdoor pools and two meadows in the centre of Kreuzberg, a sparkling mass of white and red tile, blue water and pale bodies in bright spandex, where I met Oz and where the last traces of my childhood were washed away.

Two

As he swam past, Stefan’s bone-white arm lifted out of the water, revealing his face, goggled, shaved, his air-blowing lips a soft pink ring. I was sitting with Petra and my girlfriend Maike by the low tiled wall that ran the pool’s 50-metre length, draped with colourful towels drying in the sun. I could hear the tinny sound of The Motels coming from a cassette I’d made Maike. Through the Walkman’s plastic window, I could see ‘New Songs for M’ written in Tippex next to a lumpen blob, an ugly attempt at a flower that I’d obliterated because it’d looked childish.

Maike stared down at a school copy of The Count of Monte Cristo striated with another student’s pencilled underlinings. She took so much pleasure in reading that her only prerequisite for a book was that it be long; if it was less than five hundred pages she wasn’t interested. So she consumed Stephen King and Rosamunde Pilcher as voraciously as she did Victor Hugo, Thomas Mann and Günter Grass. She squinted against the sun, her height visible in the folded leg that she clung to like a rock, her chin resting on her knee. Her damp hair, long, brown and unfashionably straight, hung around her shoulders, the tips adorned with water droplets like glass beads.

Petra lay on her front with her bikini top undone. Her ashy bob was tied into a ponytail and was dry, because she never swam at the pool – she just tanned. She wore large white-framed sunglasses and flicked through Brigitte, snorting derisively at the fashion spreads. It was always hard to tell if this glibness of hers was genuine. It certainly didn’t square with her academic successes; although Maike was always the cleverest, it was Petra who worked the hardest. She’d got the second-best Abitur grades – German A levels – in her school, and the Head of Biology at the University of Hohenheim had called her personally when he received her application.

‘Listen to this,’ Petra said, slapping my leg, as she began to read out my horoscope. Stefan passed ag

ain. The lifeguard blew his whistle at the rippling shadow of two boys who’d bombed into the water, and I saw a man emerging from the pool, water pouring from his brown back and red trunks.

The man rubbed his face and turned, and the water falling from his body shattered and steamed on the terracotta tiles. The trees behind him retained the bright green of early summer and his face, as he slicked back his black hair, was fixed in an expression of doubtful, open-mouthed concentration.

He was hairier than me, an attractive flurry across his chest and on his stomach, in his armpits as he lifted his arms to squeeze the water from his hair. A gold chain, very fine, shimmered like fish scales near his throat, and on his wrist he wore a digital watch, gold too, the link-strap brilliant with sunshine. His fingers parted and I looked down at the novel between my legs, white as tripe, and the amber hairs peeping out from the ancient elastic of my black trunks.

I knew him, or at least I’d seen him before, parked on our street, near the corner of Schiller Straße. He was there on the last day I cycled to school, sitting in a 1970s moss-green Mercedes 240D. One wrist rested on the black plastic steering wheel, the hand limp like Michelangelo’s Adam, with a cigarette between index and middle finger. The other hand was at his mouth, the nail of his middle finger touching the gap between his front teeth.

I might’ve forgotten about him, had he not still been there when I cycled home. His window was rolled down; I picked up a trace of cigarette smoke and tinny jazz music. And though I was cycling too fast to see what he was reading, I could tell from the pastel-coloured cloth that it was a hardback book without its dust jacket.

He reappeared once or twice a week, but he never noticed me; though the colour of the books changed, he never once looked up from them when I cycled past. When I saw him at the edge of the pool, though, our eyes met.

Perhaps the familiarity of Prinzenbad and my friends meant that I seemed in that moment completely comfortable with myself, and perhaps the novel between my legs made me look more adult and worldly than I felt. Because there were plenty of clues to my unworldliness. He might have noticed the biscuit-brown towel I sat on, stiff from a thousand washes, or my name in red thread on a white fabric label that had come loose on one side. He might have noticed that the book, a battered copy of Midnight’s Children, still with its plastic cover and yellow Dewey Decimal sticker, had been stolen from the school library. He might have noticed my hand-sewn towelling swimming bag, with the face of Fungus the Bogeyman sewn onto it.

I looked back down at the book, embarrassed we’d made eye contact, sweat breaking out across my back as his wet feet slapped towards me on the red tiles. I read the same line over and over again, staring at the yellowed pages warped by my damp hands. When his shadow blotted out the sun for a moment, I turned back a page, as if looking for something, and I inhaled very gently, trying to catch the smell of him, but I only got the chlorine on my body, in the pool, everywhere.

I put my back on the cool tile of the low wall and watched his figure recede as he made his way to the changing rooms. I felt anxious and inexplicably nostalgic, as if I was missing a feeling that I’d never felt.

‘Well?’ said Petra, staring back at me.

‘What?’ I said.

‘You weren’t even listening, were you?’

‘I was. You said Venus is in ascendance. And in August I need to be brave about my career,’ I said, repeating the last thing she’d read out from my horoscope.

‘You need to be brave about reading that here with all these Turks,’ Petra said, nodding at my book. ‘That’s what you need to be brave about.’

‘Why?’

‘Iran. Khomeini. Fatwa. Salman Rushdie.’

‘Have you had a stroke?’

‘The writer,’ said Petra, sitting up and tying her bikini top back on, briefly flashing the soft sides of her breasts, tanned to caramel and sparkling with sweat.

I looked at the name on the cover. I hadn’t yet got a taste for the news; it still felt like something people’s parents were interested in, and there was no internet yet to flash a constant stream of breaking stories. Back then, if you didn’t read a newspaper or watch the evening news, you remained blissfully clueless about the world beyond your apartment. ‘Is he dead?’ I said.

‘He’s not dead. They’re just trying to kill him, because it’s offensive to Islam.’

‘This?’ I said, holding up the book.

‘No.’ Petra frowned. ‘What’s that banned Salman Rushdie book?’ she asked Maike, pulling off the headphones of her Walkman, so that they fell onto her bare legs with a tinny clatter.

‘Hey!’ Maike said.

‘What’s that Salman Rushdie book that’s banned?’ Petra said again.

‘I don’t know. Didn’t Khomeini just die? Isn’t he off the hook?’

‘Satanic Verses,’ said Stefan, out of the pool, towelling himself down efficiently. Stefan’s skin was also pale, but his forearms and calves showed the tan lines of his T-shirt and shorts, the colour ending abruptly on his thighs and upper arms, like long brown socks and evening gloves.

‘Shift over,’ he said to Maike. She lay down next to me and put a cool hand on my sun-hot leg.

Stefan lay down too and put his arm over his eyes, revealing a sprig of armpit hair, so black it was almost blue. I became very aware of the physicality of my friends and my sweating body in between.

Maike took a damp strand of her hair and absently brushed it across her chin like a paintbrush. Though old friends, she and I had only been dating for a year, losing our mutual virginities early in the morning in a tent on the North Sea coast, the olive air filled with the smell of waxed canvas, unwashed hair and seawater. Although I’d applied to English universities, we’d already worked out a schedule for our continuing relationship and liked to pick out places we might live after graduation on the world map taped to the back of my bedroom door.

There is a picture of the two of us that I have on the shelf in my office at university. It’s fun, because my more perceptive students spot who it is; the first years have to read her book Wetlands: Sustainability, Construction and Structural Change in ‘Introduction to Physical Geography’. In the picture, which has that grainy softness so instantly nostalgic in the digital age, Maike and I are in Grunewald sitting on a fallen tree trunk and we’re both smiling with our eyes closed. Petra must have taken it, because I’m holding Katja, her sheepdog, on a lead. I’m wearing a large black T-shirt with an Adidas logo, white shorts, white socks and trainers, my auburn hair cut relatively short, but unstyled, a puffed, unselfconscious cap. Maike is wearing walking boots, jean shorts high on her waist and a white T-shirt with pale pink stripes. Her long hair pours off her shoulders in smooth brown strips like a river delta.

I remember liking my T-shirt and being aware that Adidas was an acceptable brand to be wearing, but I had no idea how these things made me look. Except for Petra, we all dressed carelessly, spending the money from our weekend and holiday jobs on four-season sleeping bags, microscopes, bright waterproofs and cards for the state library.

This is the last photograph I have of myself in which I look like this. After Oz, my poses close up, as if I’m trying to cover myself. I find it hard to find any photo of me up until my wedding day in which my arms are not crossed, my hand is not holding my throat or covering my mouth as if I’m trying to stop myself speaking.

It’s the same for Maike. That summer changed her too, and in every other picture I have of her – including the striking author photo on the back of Wetlands – she has flicked her long hair to the right shoulder, tipped her head, removed her glasses. I miss the artless, eyes-closed grin of the girl on the log.

‘I read Satanic Verses,’ Stefan said. ‘It’s really weird.’ Stefan had little interest in literature, but a lot of interest in politics – he was a vegetarian and a member of The Greens. The only books he read were either notoriously difficult – The Magic Mountain, Thus Spoke Zarathustra – or, like The Satanic Verses and h

is favourite book, Laughter in the Dark, in some way connected to scandal.

‘This is quite weird,’ I said, lifting up the book.

‘Suits you, Ralfi,’ he said and yawned.

The boys that had bombed into the pool ran past us spraying our hot skin with water. Petra sat up and shouted, ‘You vicious little cunts.’ The boys froze and bowed their heads sorrowfully; the younger burst into tears. ‘Oh fuck,’ Petra muttered, when the swimmers who were lined up against the wall turned to us. ‘I didn’t think they’d care.’

We laughed to protect her from outside scorn. And this might have been my lasting memory of summer 1989. Even that moment I might have forgotten, recalling only my A levels and the Wall if people asked what that year had meant to me. But of course, in the end, 1989 meant neither of those things. It just meant Oz, and espionage – how grand that word sounds now – and I suppose my family and the terrible things we did.

Three

We queued for chips and Coke before we showered, the ceiling of the tiled pool café filled with bright inflatable animals and floats, the counter lined with bread-roll halves beneath scrambled egg, sliced egg, ham and salami, a soggy pretzel letter on each. We drank and smoked in our swimming things, our bare backs sticking to the white plastic chairs, picking unhurriedly at the chips covered in both ketchup and mayonnaise – Pommes rot-weiß. We were in no rush, we had nowhere to go. We’d all finished school four weeks earlier and were enjoying the impossibly long summer before university, blissfully ignorant of what our studies would involve and how they would change us.

Stefan, Petra and Maike had gone to school together and Stefan was the son of my mother’s best friend, Beate, and had thus been my assigned playmate since birth. As a group, our friendship had been cemented in North Hessen when we were eleven and twelve at Wilde Kidz, a camp for city children with a passion for nature. You might think that city kids who were into wildlife would be an accepting cast of misfits, but it was a fortnight riven with regional antagonism. It became clear that the children from Munich and Stuttgart weren’t estranged from nature at all, and spent their weekends climbing mountains and plucking ticks from their legs in the Black Forest. The children from Frankfurt and the Ruhr had learned to light fires with sticks in the Taunus and the kids from Bremen and Hamburg could sail.

An Honest Man

An Honest Man